METFORMIN MANIA: IS IT AN ADEQUATE CHEMOPREVENTIVE AGENT FOR SKIN CANCER?

By Warren R. Heymann, MD, FAAD

Aug. 31, 2022

Vol. 4, No. 35

In managing diabetes, metformin decreases hepatic glucose output and acts as an insulin sensitizer by increasing glucose utilization by muscles and adipocytes. By improving glycemic control, serum insulin concentrations decline slightly, as do luteinizing hormone and androgen levels, thereby improving hyperinsulinemia and its signs. Additionally, metformin has platelet anti-aggregating and antioxidant effects. These pharmacological properties allow metformin to be effective in myriad disorders including cutaneous diseases such as acne, hirsutism, hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, psoriasis, skin cancer, and others. (2,3)

Generally considered safe and well-tolerated, gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) may occur in up to 30% of patients. Less frequent adverse reactions include chest discomfort, weakness, headache, rhinitis, hypoglycemia, and vitamin B12 deficiency (with long-term metformin use). There is a black box warning for lactic acidosis. This serious adverse reaction is rare (incidence of 1 in 30,000 patients) with risk factors being elderly, having a history of alcoholism, hepatic and/or renal impairment. (3)

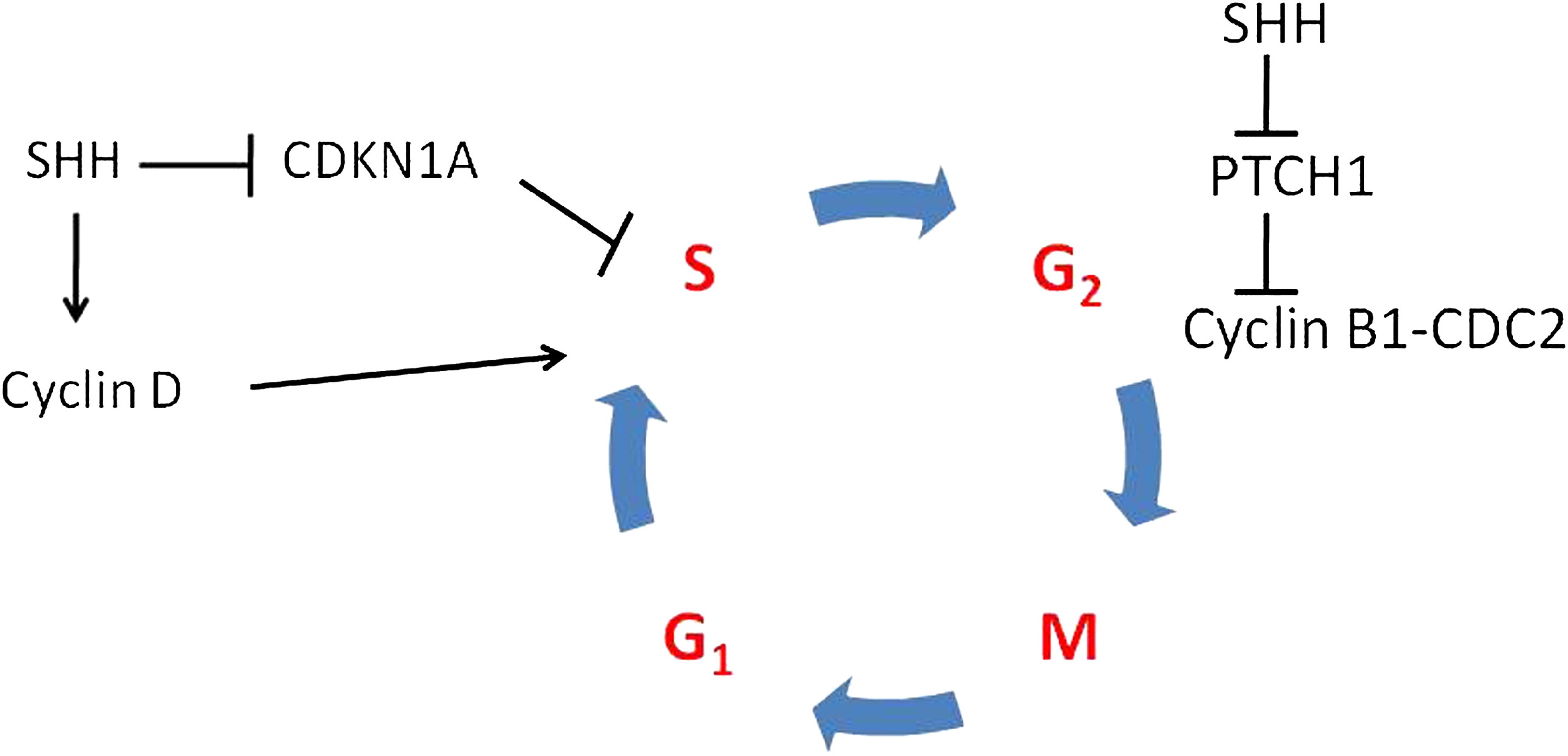

Metformin's effect on malignant tumors is controversial and its mechanism(s) of action are incompletely understood. According to Leng et al: "Epidemiological studies have shown that T2DM patients have an increased risk of liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, breast cancer and other malignant tumors. Diabetes or hyperglycemia is associated with reduced insulin sensitivity and increased expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF), which then stimulates the development of cancer." Metformin directly activates the adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway to inhibit the occurrence and development of tumors. Metformin also inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I, induces the activation of mTORC1, inhibits cyclin D, and subsequently, the growth of tumors. (4) Metformin can also directly inhibit the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway that is crucial for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) growth. (5) Additionally, "metformin indirectly inhibits tumor growth, proliferation, invasion and metastasis by decreasing blood glucose levels, attenuating insulin resistance, reducing inflammation and improving the tumor microenvironment. Glycolysis plays a critical role in the energy metabolism of tumor cells and metformin has a certain inhibitory effect on glycolysis." (4)

This commentary will focus on recent data exploring the role of metformin in cutaneous oncology.

Misitzis et al evaluated the association between metformin and keratinocyte carcinoma (KC) development in high-risk patients by performing a secondary analysis of patients enrolled in the Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial to compare risk for KC development between metformin users and non-users. Metformin-users compared to non-users had a significantly lower risk for squamous cell carcinoma with an adjusted Hazard ratio (HR: 0.45) and basal cell carcinoma (HR: 0.70). The authors concluded that patients at high risk might benefit from metformin use against a subsequent KC. (6)

Adalsteinsson et al studied the association between metformin use and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), SCC in situ (SCCis), and BCC by performing a retrospective, population-based case-control study design using all 6,880 patients diagnosed in Iceland between 2003-2017 with first-time BCC, SCCis, or invasive SCC, and 69,620 population controls. The authors found that metformin was associated with a lower risk of developing BCC (OR, 0.71), even at low doses. No increased risk of developing SCC was observed. SCCis risk was mildly elevated in the 501-1500 daily dose unit category (OR, 1.40). It is not clear why this discrepancy was observed. The authors speculate that perhaps the risk of SCC was increased because of the diabetic association, while the BCC risk decreased due to Shh inhibition. The authors concluded that the decreased risk of BCC development, even at low doses of metformin, might have potential as a chemoprotective agent for patients at high risk of BCC, although this will need confirmation in future studies. (5)

Gutkind et al studied 23 healthy, non-diabetic patients with oral premalignant lesions (OPL) with pre- and post-treatment clinical examination and biopsy. Participants received metformin for 12 weeks. Pre- and post-treatment biopsies, saliva, and blood were obtained for biomarker analysis, including immunohistochemical (IHC) assessment of mTOR signaling and exome sequencing. The clinical response rate (defined as ≥50% reduction in lesion size) was 17%. The histologic response rate (improvement in histologic grade) was 60%, including 17% complete responses and 43% partial responses. Logistic regression analysis revealed that when compared to never smokers, current and former smokers had statistically significantly increased histologic responses (p=0.016). A significant correlation existed between decreased mTOR activity (pS6 IHC staining) in the basal epithelial layer of OPL and the histological (p=0.04) and clinical (p=0.01) responses. The authors concluded that this phase II trial of metformin in individuals with OPL provided evidence that metformin administration results in encouraging histological responses and mTOR pathway modulation, warranting further investigation of metformin as a chemopreventive agent. (7)

In a meta-analysis of 6 trials involving 8,541 patients compared with controls, Chang et al reported that metformin was not significantly associated with a decreased risk of melanoma, BCC, SCC, total nonmelanoma skin cancer, or total skin cancer. (8) This nonsignificant association pattern was consistent with the random-effects meta-analysis of 4 cohort studies with 354,746 patients. The authors concluded that meta-analyses of randomized control trials and cohort studies showed no significant association between metformin and skin cancer, although suggestive evidence of modestly reduced skin cancer risks among metformin users was observed. They suggest that metformin use should not influence current medical decision making for diabetes patients at risk of developing skin cancer and that future studies are warranted to study metformin's role in skin cancer prevention.

In conclusion, despite some promising evidence that metformin may diminish the risk of skin cancer, the jury is still out. If diabetic patients are already taking metformin, they should still use their sunscreen!

Point to Remember: Although controversial, there is some increasing evidence that metformin may have some benefit in reducing the risk of skin cancer. More study is warranted before any definitive conclusion can be reached regarding its efficacy and potential use as a chemopreventive agent.

Our expert's viewpoint

Torunn E. Sivesind, MD

Robert P. Dellavalle, MD, PhD, MSPH, FAAD

Metformin was the fourth most commonly prescribed drug in the U.S. in 2019, with over 85 million prescriptions (9), and as we are all aware, skin cancer is the most common cancer in the U.S., with one in five Americans expected to develop skin cancer by age 70. (10) It doesn't take a statistician to see that any association between metformin and skin cancer, even with a small effect size, would greatly impact public health.

The 2021 study by Chang et al. (8), discussed in the above commentary, provides the most up to date and best evidence on this controversial topic. Although the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies revealed no significant association between metformin and skin cancer, the authors did note evidence of modestly reduced skin cancer risks among metformin users and suggest that further longitudinal post-marketing surveillance of RCTs and long-term follow up of large cohort studies are warranted.

Our understanding of the mechanistic actions of metformin as it relates to skin health and neoplasia continues to expand. For example, a recently published (2021) study (11) elucidated metformin's anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects for keratinocytes (KCs): in vitro, topical 0.06% metformin was shown to inhibit inflammatory markers (IL-1ꞵ, TNF-𝛼, FGF2) and to decrease cell death in UVB-challenged KCs, while in a mouse model, it was shown to reduce UVB-induced skin damage.

As noted above, multiple studies, including meta-analyses, have found a reduced risk of cancer development and improved overall cancer survival rates for various tumor types, such as colorectal, pancreatic, and prostate. (12-14) Further, its use as an adjuvant in oncologic treatment also holds promise — a recent evaluation of four melanoma cell lines found that metformin has the potential to inhibit cell proliferation and metastatic activity (15), while a meta-analysis showed a significant benefit of metformin as an adjuvant therapy among patients with colorectal and prostate cancer. (16)

Clearly, there is an abundance of evidence — granted, conflicting — that provides an impetus for further exploration of metformin's potential role in cutaneous oncology. For now, however, metformin should continue to be used for its established indications and should not be prescribed solely as a chemopreventive agent. Our real-world experience is not to prescribe metformin for skin cancer prevention — the evidence is not robust enough yet and the potential side effects are too great. A properly designed RCT showing a positive effect would be necessary to change our minds. As DermWorld Insights and Inquiries editor Dr. Heymann recently reminded us, "Careful practitioners consistently offer therapy based on the best available evidence, with the understanding that new data may immediately render current practices obsolete." (17) Here's hoping we soon have that new data!

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiriesarticles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

Skin Care Physicians of Costa Rica

Clinica Victoria en San Pedro: 4000-1054

Momentum Escazu: 2101-9574

Please excuse the shortness of this message, as it has been sent from

a mobile device.

This study endeavors to confirm what many might consider obvious…that delay of treatment for melanoma is associated with a worse outcome. The SEER database is used, which has some advantages over other large national databases but also has some very significant disadvantages, which can lead to invalid conclusions. Despite the massive study group size, several of the subgroups studied are small in number, which may also affect validity of conclusions. So, reader beware.

The primary outcomes evaluated included overall mortality (OM) and melanoma specific mortality (MSM) as they relate to delay of definitive excisional treatment. Whenever I read this kind of paper pertaining to melanoma, I focus most intensely on melanoma specific data. In many such studies, the data that is not specific to melanoma tends to have overwhelming, uncontrolled, and confounding variables such that it renders these data points much less useful. As such, I will focus on MSM in review of this paper.

Of all patients studied, approximately 77% were definitively treated within 1 month. This is probably a reasonable minimum standard that all entities can begin with to improve the quality of care provided to their melanoma patients.

Their findings show that cumulatively, univariate analysis of delays in definitive treatment show increased MSM for melanoma stages I, II, and III, with the most profound effect in stage I melanoma. On multivariate analysis, increasing delays still increased the hazard ratio of MSM for all stages. Of all variables assessed, Breslow's thickness is associated with the most profound increase in MSM. Again, stage I tumors with delayed treatment were the most profoundly affected in terms of MSM. Interestingly, stage III melanomas did not demonstrate statistically significant association between treatment delay and MSM. Also of note, OM was significantly worse for stage I patients even with as little as 1 month treatment delay.

To summarize, again focusing on MSM rather than OM, treatment delays may be associated with worsened MSM, and most significantly for stage I tumors. Their capsule summary concludes that, "patients with stage I disease suffer significantly worsened melanoma specific and overall mortality with treatment delays beyond 30 days." As such, this study emphasizes the importance of surgical wait times as an important datapoint for quality assurance.