S aureus en DA

Updated understanding of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis: from virulence factors to commensals and clonal complexes

SOURCE : Experimental dermatology

In this single-center, retrospective cohort study, 28 patients with diagnoses of skin picking, acne excoriée, or neurodermatitis were treated with N-acetylcysteine. In all, 13 patients completed an adequate trial, defined as a minimum dose of 600 mg twice daily for 3 consecutive months. Of these 13 patients, 61.5% had documented improvement on physical exam. The most common side effect was GI upset (7.1%). The discontinuation rate prior to completion of an adequate trial was 53.6%, with 40% of patients discounting treatment due to a lack of response.

Dr Caroline Ward

Dr Caroline Ward, GP and standing member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Managing Common Infections Advisory Committee, discusses NICE recommendations on the treatment of atopic eczema, focusing on eczema complicated by bacterial or viral infection.

Read this article to learn more about:

Stepped treatment options for the management of atopic eczema

When to prescribe antibiotics, and antibiotic choice in children and adults

Red flags for referral or hospital admission

Atopic eczema is a chronic, itchy, inflammatory skin condition characterised by flares and remissions; however, in severe eczema, symptoms may be continuous.[1] Although atopic eczema can affect people of all ages, it presents most frequently in children, with 70–90% of cases occurring before 5 years of age.[1] The condition resolves in about 65% of children by 7 years of age, and in about 74% of children by 16 years of age.[2]

A 'stepped approach' is recommended by NICE for the management of eczema, with treatment stepped up or down according to the current severity of the condition.[1],[3] NICE categorises eczema as mild, moderate, or severe (see Box 1).[4],[5]

Mild: areas of dry skin, infrequent itching (with or without small areas of redness)

Moderate: areas of dry skin, frequent itching, redness (with or without excoriation and localised skin thickening)

Severe: widespread areas of dry skin, incessant itching, redness (with or without excoriation, extensive skin thickening, bleeding, oozing, cracking and alteration of pigmentation).

© NICE 2021. Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/cg57

© NICE 2021. Eczema—atopic: scenario, assessment. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/management/assessment/

All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details.

Topical emollients are the mainstay of treatment for all patients with eczema; they should be used liberally and regularly, even when skin is clear, and their use should be increased during a flare.[6] Patients with eczema should be advised to treat areas of eczema with unperfumed emollients to avoid skin reactions associated with additives in some emollients; they should also avoid the use of soaps, instead using a soap substitute such as an emollient for washing.[6]

Topical corticosteroids should usually be used once or twice a day for flares of eczema, and continued for 48 hours after the flare has been controlled.[7] Topical corticosteroids are available in four potencies: mildly potent, moderately potent, potent, and very potent. The potency prescribed should be tailored to the severity of symptoms and area of the body involved.[7] The face, genitals, and flexures are considered delicate areas of skin; thus, mild-potency steroids should usually be tried first line in these areas, aiming for a maximum duration of 5 days' use.[7] Very potent preparations are usually only used under specialist dermatological advice, especially in children.7

Table 1 shows the stepped approach advocated by NICE for mild, moderate, and severe eczema, and Table 2 shows the topical corticosteroids that are available for each of the four potencies.[3],[7],[8]

| Mild atopic eczema | Moderate eczema[A] | Severe eczema |

|---|---|---|

| Emollients | Emollients | Emollients |

| Mild potency topical corticosteroids | Moderate potency topical corticosteroids | Potent topical corticosteroids |

| – | Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus)[B] | Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus)[B] |

| – | Bandages[B] | Bandages[B] |

| – | – | Phototherapy[C] |

| – | – | Oral corticosteroids[D] |

| [A] If there is severe itch or urticartia, consider prescribing a one-month trial of a non-sedating antihistamine (such as cetirizine, loratadine, or fexofenadine. Review the use of non-sedating antihistamines every 3 months (treatment can be stopped, then restarted if symptoms worsen).[8] [B] Usually only prescribed by a specialist (for example, a GP with a specialist interest in dermatology, a dermatologist, or a paediatrician). [C] Phototherapy is available in secondary care for the treatment of very severe eczema that has proved resistant to standard treatment. Systemic immunosuppressants (for example, ciclosporin and azathioprine) are also available in secondary care for the same indication. [D] Oral corticosteroids can be prescribed short-term in primary care for severe flares. Other systemic treatments suitable for maintenance of severe eczema (for example, ciclosporin or azathioprine) require referral to secondary care. | ||

| © NICE 2021. Eczema—atopic: NICE stepped approach to treatment. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/prescribing-information/stepped-approach-to-treatment/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | ||

| Potency | Topical corticosteroid |

|---|---|

| Mildly potent | Hydrocortisone 0.1%, 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.5%[B] |

| Moderately potent | Betamethasone valerate 0.025% (Betnovate-RD®) Clobetasone butyrate 0.05% (Eumovate®) |

| Potent | Betamethasone valerate 0.1% (Betnovate®) Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% (Diprosone®) |

| Very potent[C] | Clobetasol propionate 0.05% (Dermovate®) Diflucortolone valerate 0.3% (Nerisone Forte®) |

| [A] See the British National Formulary ( bnf.nice.org.uk ) for a complete list of all topical corticosteroids available in the UK. [B] Hydrocortisone 1% is available over the counter for mild-to-moderate eczema not involving the face or genitals. [C] Very potent topical corticosteroids should usually only be prescribed by specialists. | |

| © NICE 2021. Eczema—atopic: topical corticosteroids. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/prescribing-information/topical-corticosteroids/ All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | |

Regarding the treatment of mild eczema, NICE recommends prescribing a mild topical corticosteroid for areas of red skin. Active follow up is rarely required for mild eczema.[9]

A moderately potent topical corticosteroid can be used for the treatment of moderate eczema if skin is inflamed, although on delicate areas of skin it may be more appropriate to start with a mild-potency corticosteroid.[8] In patients with severe itch or urticaria, a 1-month trial of a non-sedating antihistamine (for example, cetirizine, loratadine, or fexofenadine) may be of benefit.[8]

Consider the need for referral to dermatology if skin is not responding as expected, or hospital admission if there are signs and symptoms of eczema herpeticum.[8]

For the management of severe eczema, a potent topical corticosteroid should be used on inflamed areas. For delicate areas of skin, use a moderate-potency corticosteroid, and aim for a maximum of 5 days' use.[10]

Severe itch or urticaria may be managed with a 1-month trial of a non-sedating antihistamine. If itching is interrupting sleep, a short course (maximum 2 weeks) of a sedating antihistamine (for example, chlorphenamine) can be prescribed.[10]

In adults with severe, extensive eczema causing psychological distress, a short course of an oral corticosteroid such as 30 mg prednisolone for 7 days may be beneficial.10 However, there are no data from controlled trials on the use of oral corticosteroids in this scenario, and NICE recommends referral for children aged under 16 years with severe, extensive eczema causing psychological distress.[10]

Patients with severe eczema should be referred for a routine dermatology appointment if:[10]

the diagnosis is, or has become, uncertain

current management has not controlled eczema satisfactorily

facial eczema has not responded to treatment

treatment application advice is needed

contact allergic dermatitis is suspected

there is recurrent secondary infection

eczema is causing significant social or psychological problems.

Admit to hospital if eczema herpeticum (Figure 1) is suspected.[10]

Figure 1: Eczema herpeticum

Figure 1: Eczema herpeticum

© DermNet New Zealand. Reproduced with permission.

Eczema can be complicated by either viral or bacterial infection. Superficial fungal infections are also more common in people with eczema than in those without.[1]

Eczema herpeticum is caused by widespread infection with the herpes simplex (cold sore) virus, and is considered a medical emergency.[4],[11],[12] Disseminated eczema herpeticum presents with areas of painful, worsening eczema and small clustered uniform blisters, which may coalesce and lead to extensive lesions and large areas of desquamation and bleeding (see Figure 1).[12] In its more localised form, herpes simplex infection typically presents with grouped vesicles, but punched-out erosions may also occur.[4],[13] A diagnosis of eczema herpeticum should be considered if infected eczema fails to respond to treatment with antibiotics and an appropriate topical corticosteroid.[4],[11]

If eczema herpeticum is suspected, treatment with oral aciclovir should be started; in addition, NICE advises that children with suspected eczema herpeticum are referred for same-day specialist dermatological advice.[14] Children with eczema herpeticum are often systemically unwell with fever, lymphadenopathy, and malaise, and require urgent referral to hospital.[12],[13]

Eczema is often colonised with bacteria, but may not be clinically infected.[11] Infection is commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, and may present as rapidly worsening eczema or failure to respond to treatment.[11] There may also be weeping, pustules, crusts, fever, and malaise.11 However, not all eczema flares are caused by a bacterial infection, even if weeping and crusts are present, and flares not caused by bacterial infection will not respond to antibiotics.[11] Evidence shows a limited benefit of antibiotics even when typical signs and symptoms of infection are present.[11]

Given that—even when typical signs and symptoms of infection are present (for example, crusting, weeping, or pustules)—the evidence shows limited benefits of antibiotics in addition to usual care with emollients and topical steroids, antibiotics should not be routinely offered to patients who are systemically well.[11] Antibiotics should only be used when the infection is severe, the patient is systemically unwell with fever and/or malaise, or they are at increased risk of complications (for example, people who are immunosuppressed).11

The treatment options for infected eczema are presented in Tables 3 and 4.[11]

| Treatment | Antibiotic, dosage and course length |

|---|---|

| For secondary bacterial infection of eczema in people who are not systemically unwell | Do not routinely offer either a topical or oral antibiotic |

| First choice topical if a topical antibiotic is appropriate | Fusidic acid 2%: Apply three times a day for 5 to 7 days For localised infections only. Extended or recurrent use may increase the risk of developing antimicrobial resistance |

| First choice oral if an oral antibiotic is appropriate | Flucloxacillin: 500 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days |

| Alternative oral antibiotic if the person has a penicillin allergy or flucloxacillin is unsuitable | Clarithromycin: 250 mg twice a day for 5 to 7 days The dosage can be increased to 500 mg twice a day for severe infections |

| Alternative oral antibiotic if the person has a penicillin allergy or flucloxacillin is unsuitable, and the person is pregnant | Erythromycin: 250 mg to 500 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days |

| If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected or confirmed | Consult a microbiologist |

| © NICE 2021. Secondary bacterial infection of eczema and other common skin conditions: antimicrobial prescribing. www.nice.org.uk/ng190 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | |

| Treatment | Antibiotic, dosage and course length |

|---|---|

| For secondary bacterial infection of eczema in people who are not systemically unwell | Do not routinely offer either a topical or oral antibiotic |

| First choice topical if a topical antibiotic is appropriate | Fusidic acid 2%: Apply three times a day for 5 to 7 days For localised infections only. Extended or recurrent use may increase the risk of developing antimicrobial resistance |

| First choice oral if an oral antibiotic is appropriate | Flucloxacillin (oral solution or capsules): 1 month to 1 year: 62.5 mg to 125 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days 2 years to 9 years: 125 mg to 250 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days 10 years to 17 years: 250 mg to 500 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days |

| Alternative oral antibiotic if the person has a penicillin allergy or flucloxacillin is unsuitable | Clarithromycin: 1 month to 11 years:

12 years to 17 years:

|

| Alternative oral antibiotic if the person has a penicillin allergy or flucloxacillin is unsuitable, and the person is pregnant | Erythromycin: 8 years to 17 years: 250 mg to 500 mg four times a day for 5 to 7 days |

| If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected or confirmed | Consult a local microbiologist |

| © NICE 2021. Secondary bacterial infection of eczema and other common skin conditions: antimicrobial prescribing. www.nice.org.uk/ng190 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication. See www.nice.org.uk/re-using-our-content/uk-open-content-licence for further details. | |

The following points should be noted and discussed with patients/carers when considering initiation of antibiotic treatment:11

The evidence, which suggests limited benefits of antibiotics

The risk of antimicrobial resistance with repeated courses of antibiotics

Possible side-effects.

Whether or not an antibiotic is given, advise the patient to continue with regular treatments such as emollients and topical steroids, and to seek medical help if symptoms worsen rapidly or significantly at any time.11

A topical antibiotic is usually more appropriate than an oral antibiotic if the person is not systemically unwell, and if the infection is localised and not severe.[11] Fusidic acid 2% should be prescribed as the first-line topical antibiotic. Other topical treatments, such as mupirocin, should be reserved for specific indications such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) decolonisation.[11] If fusidic acid is unsuitable or ineffective, an oral antibiotic would be a more suitable choice.[11]

An oral antibiotic rather than a topical antibiotic is more appropriate if the person is systemically unwell, or if the infection is widespread or severe.11

Some children may not tolerate flucloxacillin solution because of its unpleasant taste, in which case tablets or capsules can be considered. There are some useful resources available for parents to encourage children to swallow tablets or capsules (for example, the Medicines for Children leaflet Helping your child to swallow tablets, available at: bit.ly/3wAQWFG ). For children who are unable to swallow capsules, one of the alternative oral antibiotics would be suitable.[11]

To reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance and adverse effects, the shortest course of an antibiotic that is likely to be effective should be prescribed.[11] Five to 7 days of treatment should be sufficient to treat secondary bacterial infection of eczema.[11] In the past, NICE recommended the use of fusidic acid 2% for 1–2 weeks; however, a shorter duration of 5–7 days is now recommended in order to provide effective treatment while reducing the risk of resistance.[11]

A skin swab is not routinely recommended at the initial presentation of infected eczema.[11] Eczema is often colonised with bacteria, and may not be clinically infected. Therefore, there is a possibility of culturing and identifying colonising rather than infective bacteria, and subsequent initiation of inappropriate or unnecessary antibiotics.11

A skin swab should be considered if:[11]

infection is worsening or has not improved as expected after first-line antibiotic treatment

a patient has frequent recurrences of infected eczema. This may help to guide future antibiotic choice if the person has a resistant infection. In this instance, you should also consider taking a nasal swab to check for Staphylococcus aureus, which may indicate MRSA carriage; if found, start treatment for decolonisation as per local guidelines or microbiology advice.

If a skin swab has been sent off for microbiological testing, the results should be reviewed when available and the antibiotic changed according to the results if symptoms are not improving, using a narrow-spectrum antibiotic if possible.[11]

Patients should be referred to hospital if they have any signs or symptoms suggestive of a more serious illness or condition, such as sepsis, or necrotising fasciitis.[11]

Consider referral or specialist advice for patients with infected eczema if they have spreading infection that is not responding to oral antibiotics, are systemically unwell, are at high risk of complications, or have infections that recur frequently.[11]

Patients should be advised to return for reassessment if they become systemically unwell, develop severe pain, or their symptoms have not improved after a complete course of antibiotics.[11]

If patients do present for reassessment, consider other possible diagnoses, such as viral infection (for example, eczema herpeticum), more serious conditions (such as cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis, or sepsis), or treatment failure due to the development of resistant bacteria as a result of previous antibiotic use.[11]

The mainstay of treatment for all severities of eczema should be liberal and frequent use of topical emollients, even when skin is clear, and to be continued during flares. Additional treatments, such as topical steroids, should be tailored to the severity of the presenting symptoms and signs, then treatment stepped down once symptoms improve. Evidence shows a limited benefit of antibiotic use even when typical symptoms and signs of infection are present. Therefore, antibiotics should usually be reserved for those who are systemically unwell, at increased risk of complications, or with severe infection.

Written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon.

The following implementation actions are designed to support STPs and ICSs with the challenges involved with implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you to consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

Review local care pathways for the management of eczema

Update local formularies with choices of emollients and other topical preparations for eczema treatment

Consider publishing information leaflets explaining the correct use of topical preparations on local formulary websites that can be downloaded and given to patents

Ensure that local referral guidelines identify indications for referral to specialist care, and how this can be accessed urgently if required

Include treatment of possible infected eczema in any local antimicrobial stewardship guidelines to avoid excessive antibiotic use.

STP=sustainability and transformation partnership; ICS=integrated care system

This article was first published by Guidelines in Practice, part of the Medscape Professional Network. To read more articles on implementing clinical guidelines, visit guidelinesinpractice.co.uk. For clinical guideline summaries, visit guidelines.co.uk.

NICE. Eczema—atopic: summary. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

Primary Care Dermatology Society. Atopic eczema. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/atopic-eczema (accessed 25 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: NICE stepped approach to treatment. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/prescribing-information/stepped-approach-to-treatment/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management. Clinical Guideline 57. NICE, 2007 (last updated 2021). Available at: www.nice.org.uk/cg57

NICE. Eczema—atopic: scenario, assessment. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/management/assessment/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: emollients. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/prescribing-information/emollients/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: topical corticosteroids. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/prescribing-information/topical-corticosteroids/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: scenario, moderate eczema. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/management/moderate-eczema/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: scenario, mild eczema. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/management/mild-eczema/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Eczema—atopic: scenario, severe eczema. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/management/severe-eczema/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

NICE. Secondary bacterial infection of eczema and other common skin conditions: antimicrobial prescribing. NICE Guideline 190. NICE, 2021. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/ng190

NICE. Eczema—atopic: what are the complications? NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/background-information/complications/ (accessed 20 May 2021).

Lyons, J, Milner, J, Stone, K. Atopic dermatitis in children: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2015; 35 (1): 161–183.

NICE. Treatment of eczema herpeticum. Quality Statement 7: treatment of eczema herpeticum. Quality Standard 44. NICE, 2007 (last updated 2021). Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs44/chapter/Quality-statement-7-Treatment-of-eczema-herpeticum

© 2021 WebMD, LLC

Send comments and news tips to uknewsdesk@medscape.net.

Cite this: Adopt a Stepped Approach to Atopic Eczema Management - Medscape - Jul 13, 2021.

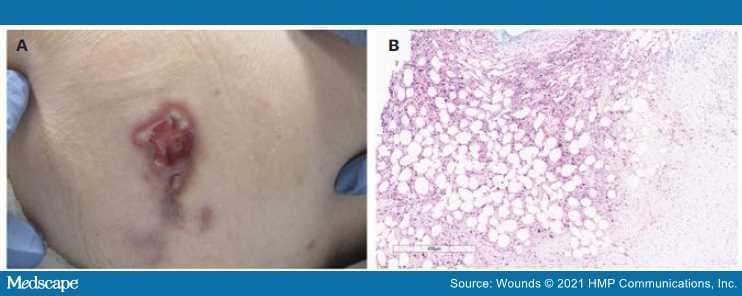

Introduction: This case of herpes virus–induced panniculitis originally diagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) illustrates the need for a high index of suspicion for atypical causes of cutaneous ulcers in patients who are immunocompromised.

Case Report: A 79-year-old male presented with a 3-month history of a painless chronic ulcer on the left buttock that was refractory to antibiotic therapy and intralesional corticosteroid. The medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus type 2 and rheumatoid arthritis managed with long-term methotrexate and low-dose prednisone. Because the patient initially had a painful and enlarging skin ulcer after intralesional treatment with corticosteroids, an undermined and violaceous ulcer, and an autoimmune condition, PG was suspected at the initial evaluation. A subsequent skin biopsy to complete the workup confirmed the unexpected diagnosis of herpetic panniculitis. The patient was started on antiviral therapy; a prolonged therapeutic and suppressive dose was required. This case highlights the importance of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of chronic ulcers to rule out infectious etiologies. Maintaining a high index of suspicion for rare causes of cutaneous ulcers in the patient with immunosuppression is paramount.

Conclusions: Herpes virus infection is only one atypical cause of ulcerative nodules in the immunocompromised patient. Skin biopsy should be considered in the immunocompromised patient with presumed PG that is not responding to standard of care treatment.

The nonspecific clinical presentation of panniculitides requires clinical pathological correlation to determine the etiology. Infection-induced panniculitis is often seen in the immunocompromised patient and presents as 1 or more fluctuant nodules that ulcerate on the lower extremities.[1] Infection with herpes virus usually presents as an easily distinguishable vesicular rash. In the patient with immunosuppression, however, herpes virus infection can manifest with uncommon clinical findings.[2] The 2 subtypes of infection-induced panniculitis are primary, that is, a direct infection into the fat tissue, and secondary, which occurs through hematogenous spread of the pathogen.[3,4] However, the presence of ulcerative nodules may also be suggestive of the presence of other underlying etiologies, such as medium-sized vasculitis and vasculopathies (eg, calciphylaxis), factitial etiology, or inflammatory ulcerations (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum [PG]).

A 79-year-old male with a history of diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis undergoing treatment with methotrexate 15 mg per week and prednisone 7.5 mg per day presented with a 3-month history of a mostly nontender chronic ulcer on the left buttocks that was refractory to wound care and antibiotic therapy. Physical examination revealed a 1.4 cm × 2.7 cm deep skin ulcer with violaceous borders. Superficial bacterial wound cultures were negative. Ultrasonography revealed no fluid collections. According to the diagnostic criteria proposed by Su et al[5] for PG, the patient's progressive skin ulcer with irregular undermining and violaceous border qualified as major criteria and the history of an autoimmune condition qualified as a minor criterion. As the diagnosis of PG was suspected, the ulcer was treated with intralesional triamcinolone.

Two weeks later, the ulcer had not improved. Instead, it had become tender, increased in size, and developed accentuated, bizarre borders and surrounding small nodules suggestive of possible pathergy. To complete the workup of this atypical ulcer, a punch biopsy of the edge of the ulcer was done, which revealed extensive necrosis within the subcutis as well as a diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and histiocytes suggestive of an infectious or inflammatory etiology. Staining for herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 highlighted many cells in areas of fat necrosis (Figure). Staining for varicella-zoster virus (human herpesvirus 3) was negative. Results of additional, special stains and microbial cultures for fungal (periodic acid-Schiff technique), bacterial (Gram stain), and acid-fast mycobacterial (Fite method) organisms were negative. These findings supported the diagnosis of herpetic panniculitis. Polymerase chain reaction testing of a subsequent herpetic flare on the anterior leg confirmed the diagnosis of herpes simplex virus 2. The patient had an unknown history of shingles and herpes complex infection.

Figure.

(A) Ulcerative nodule with violaceous erythema, undermining, and slight elevation of borders with some fibrinous exudate on left hip. (B) High-power view of the subcutis demonstrating positive HSV 1/2 staining with extensive adipocyte necrosis.

HSV: herpes simplex virus

A 4-week course of valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily was started based on kidney function. The lesion on the left buttock began improving but had not completely resolved by 4-week follow-up. An infectious disease specialist was consulted, who recommended an extended course of valacyclovir 500 mg twice a day to complete up to 8 weeks of treatment, transitioning to prophylaxis dosing with valacyclovir 500 mg for 1 year. At the 3-month follow-up visit, the lesions were improved. Time to complete healing was approximately 6 months.

This case is comparable to the only previously published case (to the authors' knowledge) of herpes virus leading to panniculitis, including that both patients received immunosuppressive therapy.[6] In the patient reported on by Tomasini and Ribero,[6] however, the ulcer completely regressed after 1 month of treatment with acyclovir. In comparison, although the patient in this case had shown some improvement with after 4 weeks of valacyclovir 500 mg daily, new lesions continued to develop, which prompted an increased dose to 1000 mg daily. This patient began showing improvement of all ulcers after a 10-day course of the increased dose.

Importantly, the patient in this case was initially and erroneously given a clinical diagnosis of PG; subsequent pathology results led to the final diagnosis of herpetic panniculitis. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare condition that commonly presents as a full-thickness ulcer with bluish purple undermining borders and can have white cell debris that looks like pus but often shows no growth on culture.[7] There have been prior reports of herpes virus infection mimicking PG.[8–12] However, none of these cases resulted in panniculitis. Distinguishing early PG from panniculitis can be challenging in clinical practice.[13]

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a clinical diagnosis arrived at only after infection, malignancy, and trauma have been ruled out.[14] The pathology of PG is nonspecific, but biopsies can help rule out similar clinical presentations, such as vasculitides and malignant abnormalities.[14] Other causes of cutaneous ulcers that may mimic PG include arterial and venous disease, vascular occlusion, hematologic causes, calciphylaxis, drug-induced ulceration, hypertension (Martorell ulcer), and inflammatory disorders such as cutaneous Crohn's disease.[15]

This case provides another example of herpes virus induced panniculitis in an immunocompromised patient and highlights a not uncommon clinical scenario of misdiagnosis of an atypical ulcer. The chance for misdiagnosis also highlights the importance of performing biopsy on all patients with presumed PG and maintaining a high index of suspicion for rare causes of cutaneous ulcers in those who are immunocompromised. Additionally, this case suggests that not all cases of herpes virus induced panniculitis resolve quickly even when treated with appropriate antivirals and that long term and prophylactic treatment may be indicated in some cases.

Given that this is a single case study, the strength of the conclusions is limited. Several limitations led to an initial misdiagnosis of PG and, ultimately, a delay in appropriate treatment for herpetic panniculitis. The patient's autoimmune disease coupled with the wound morphology, for example, the violaceous wound border, was suggestive of PG according to the Su et al[5] criteria. The diagnosis of PG was made prior to performing immunohistochemical staining and obtaining tissue culture results. However, given the incidence of PG (3 to 10 patients per million population per year) and the rarity of herpetic panniculitis, empiric treatment for PG was warranted.[16] The lesions of the patient reported herein drastically worsened when treated empirically with intralesional triamcinolone, which prompted further workup described in the case.

Atypical presentations of herpes virus can manifest in patients who are immunocompromised and may result in infection-induced panniculitis. Additionally, skin biopsies should be considered in patients with chronic ulcers (especially in such patients who are immunocompromised) that are not responsive to standard of care treatment to rule out ulcerative conditions of infectious etiology. Treatment should consist of antiviral therapy that is active against herpes virus. Long-term treatment may be needed.

Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, Ko CJ. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

Johnson R, Dover J. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; 1993:2637.

Morrison LK, Rapini R, Willison CB, Tyring S. Infection and panniculitis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(4):328–340. doi:10.1111/j.1529–8019.2010.01333.x

Johansson L, Thulin P, Low DE, Norrby-Teglund A. Getting under the skin: the immunopathogenesis of Streptococcus pyogenes deep tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(1):58–65. doi:10.1086/653116

Su WPD, Davis MDP, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(11):790–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x

Tomasini CF, Ribero S. Herpes infection: from skin to panniculitis involvement. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019;154(2):224–226. doi:10.23736/S0392-0488.17.05700–5

Pompeo MQ. Pyoderma gangrenosum: recognition and management. Wounds. 2016;28(1):7–13.

Lau H, Lee ACW, Tang SK. Isolated foot ulcer complicating acute leukemia: an unusual manifestation of herpes simplex virus infection simulating pyoderma gangrenosum. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20(6):477–480.

Kumar LS, Shanmugasekar C, Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR. Herpes misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2009;30(2):106–108. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.62768

Brown TS, Callen JP. Atypical presentation of herpes simplex virus in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cutis. 1999;64(2):123–125.

Wahba A, Cohen HA. Herpes simplex virus isolation from pyoderma gangrenosum lesions in a patient with chronic lymphatic leukemia. Dermatologica. 1979;158(5):373–378. doi:10.1159/000250783

Saunderson RB, Tng V, Watson A, Scurry J. Perianal herpes simplex virus infection misdiagnosed with pyoderma gangrenosum: case of the month from the Case Consultation Committee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20(2):e14–e15. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000178

Mortazavi H, Soori T, Azizpour A, Goodarzi A, Nikoo A. Photoclinic. Infection-induced panniculitis. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(9):649–650.

Reichel S, Kushner J, LaFond AA. Nonhealing lower leg ulcers. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(1):81–82. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3400

George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum - a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(3):224–228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(9):1008–1017. doi:10.1111/j.1468–3083.2009.03199.x

Wounds. 2021;33(5):E39-E41. © 2021 HMP Communications, LLC

Cite this: Pyoderma Gangrenosum-Like Presentation of Herpetic Panniculitis in a Patient With Immunosuppression - Medscape - May 01, 2021.

A diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in individuals ages 15 years or older, compared with controls without atopic dermatitis, was nearly twice as likely to be associated with autoimmune disease, in a case control study derived from Swedish national health care registry data.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is known to be associated with other atopic conditions, and there is increasing evidence it is associated with some nonatopic conditions, including some cancers, cardiovascular disease, and neuropsychiatric disorders, according to Lina U. Ivert, MD, of the dermatology and venereology unit at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, and coauthors. There are also some data indicating that autoimmune diseases, particularly those involving the skin and gastrointestinal tract, are more common in people with AD.

The aim of their study, published in the British Journal of Dermatology, was to investigate a wide spectrum of autoimmune diseases for associations with AD in a large-scale, population-based study using Swedish registers. Findings could lead to better monitoring of comorbidities and deeper understanding of disease burden and AD pathophysiology, they noted.

With data from the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare's National Patient Register on inpatient diagnoses since 1964 and specialist outpatient visits since 2001, the investigators included all patients aged 15 years and older with AD diagnoses (104,832) and matched them with controls from the general population (1,022,435). The authors noted that the large number of people included in the analysis allowed for robust estimates, and underscored that 80% of the AD patients included had received their diagnosis in a dermatology department, which reduces the risk of misclassification.

The investigators found an association between AD and autoimmune disease, with an adjusted odds ratio) of 1.97 (95% confidence interval, 1.93-2.01). The association was present with several organ systems, particularly the skin and gastrointestinal tract, and with connective tissue diseases. The strongest associations with autoimmune skin diseases were found for dermatitis herpetiformis (aOR, 9.76; 95% CI, 8.10-11.8), alopecia areata (aOR, 5.11; 95% CI, 4.75-5.49), and chronic urticaria (aOR, 4.82; 95% CI, 4.48-5.19).

AD was associated with gastrointestinal diseases, including celiac disease (aOR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.84-2.09), Crohn disease (aOR 1.83; CI, 1.71-1.96), and ulcerative colitis (aOR 1.58; 95% CI, 1.49-1.68).

Connective tissue diseases significantly associated with AD included systemic lupus erythematosus (aOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.42-1.90), ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.29-1.66), and RA (aOR, 1.44; 95% CI,1.34-1.54]). Hematologic or hepatic autoimmune disease associations with AD were not observed.

The association between AD and two or more autoimmune diseases was significantly stronger than the association between AD and having one autoimmune disease. For example, the OR for AD among people with three to five autoimmune diseases was 3.33 (95% CI, 2.86-3.87), and was stronger in men (OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 2.92-5.37) than in women (OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 2.63-3.74).

In the study overall, the association with AD and autoimmune diseases was stronger in men (aOR, 2.18; 95% CI, 2.10-2.25), compared with women (aOR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.85-1.93), but this "sex difference was only statistically significant between AD and RA and between AD and Celiac disease," they noted.

Associations between AD and dermatomyositis, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, Hashimoto's disease, Graves disease, multiple sclerosis, and polymyalgia rheumatica were found only in women. Ivert and coauthors observed that "women are in general more likely to develop autoimmune diseases, and 80% of patients with autoimmune diseases are women."

Commenting on the findings, Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, said, "At a high level, it is important for clinicians to recognize that atopic dermatitis is a systemic immune-mediated disease. AD is associated with higher rates of comorbid autoimmune disease, similar to psoriasis and other chronic inflammatory skin diseases."

"At this point, there is nothing immediately actionable about these results," noted Silverberg, who was not an author of this study. "That said, in my mind, they raise some provocative questions: What is the difference between AD in adults who do versus those who do not get comorbid autoimmune disease? Does AD then present differently? Does it respond to the same therapies? These will have to be the subject of future research."

The study was funded by the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association Research Foundation, Hudfonden (the Welander-Finsen Foundation), and the Swedish Society for Dermatology and Venereology. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ivert LU et al. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Oct 22. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19624.

This article originally appeared on MDedge.com, part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Medscape Medical News © 2021 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Swedish Registry Study Finds Atopic Dermatitis Significantly Associated With Autoimmune Diseases - Medscape - Jan 05, 2021.

Obesity, atopic dermatitis, psychiatric disease, and arthritis are the most common comorbidities among infants, children, and adolescents with psoriasis, while predictors of moderate to severe disease include morphology, non-White race, and culture-confirmed infection.

Those are among the key findings from a retrospective analysis of pediatric psoriasis patients who were seen at the University of California, San Francisco, over a 24-year period.

Carmel Aghdasi

"Overall, our data support prior findings of age- and sex-based differences in location and morphology and presents new information demonstrating associations with severity," presenting study author Carmel Aghdasi said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. "We provide evidence of the increased use of systemic and biologic therapies over time, an important step in ensuring pediatric patients are adequately treated."

To characterize the demographics, clinical features, comorbidities, and treatments, and to determine predictors of severity and changes in treatment patterns over 2 decades in a large cohort of pediatric psoriasis patients, Aghdasi, a 4th-year medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues retrospectively evaluated the records of 754 pediatric patients up to 18 years of age who were seen at UCSF for psoriasis from 1997 to 2021. They collected demographic, clinical, familial, comorbidity, and treatment data and divided the cohort into two groups by date of last visit.

Group 1 consisted of 332 patients whose last visit was between 2001 and 2011, while the second group included 422 patients whose last visit was between 2012 and 2021. The researchers also divided the cohort into three age groups: infants (0-2 years of age), children (3-12 years of age), and adolescents (13-18 years of age).

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were female and 67% presented between ages 3 and 12. (Seventy-four patients were in the youngest category, 0-2 years, when they presented.) The average age of disease onset was 7 years, the average age at presentation to pediatric dermatology was 8.8 years, and 37% of the total cohort were overweight or obese. The top four comorbidities were being overweight or obese (37%), followed by atopic dermatitis (19%), psychiatric disease (7%), and arthritis (4%).

Plaque was the most common morphology (56%), while the most common sites of involvement were the head and neck (69%), extremities (61%), and trunk (44%). About half of the cohort (51%) had mild disease, 15% had culture-confirmed infections (9% had Streptococcal infections), and 66% of patients reported itch as a symptom.

The researchers observed that inverse psoriasis was significantly more common in infants and decreased with age. Anogenital involvement was more common in males and in those aged 0-2, while head and neck involvement was more common in females. Nail involvement was more common in childhood.

Topical therapy was the most common treatment overall and by far the most common among those in the 0-2 age category. "Overall, phototherapy was used in childhood and adolescents but almost never in infancy," Ms. Aghdasi said. "Looking at changes in systemic treatment over time, conventional systemic use increased in infants and children and decreased in adolescents. Biologic use increased in all ages, most notably in children aged 3-12 years old."

Multivariate regression analyses revealed that the following independent variables predicted moderate to severe psoriasis: adolescent age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.9; P = .03), guttate morphology (aOR, 2.2; P = .006), plaque and guttate morphology (aOR, 7.6; P less than .001), pustular or erythrodermic morphology (aOR, 5; P = .003), culture-confirmed infection (aOR, 2; P = .007), Black race (aOR, 3.3; P = .007), Asian race (aOR, 1.8; P = .04, and Hispanic race (aOR, 1.9; P = .03).

Dr Kelly Cordoro

"Further analysis is needed to elucidate the influence of race on severity and of the clinical utility of infection as a marker of severity," Ms. Aghdasi said. "Interestingly, we did not find that obesity was a marker of severity in our cohort."

In an interview, senior study author Kelly M. Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at UCSF, noted that this finding conflicts with prior studies showing an association between obesity and severe psoriasis in children.

"Though methodologies and patient populations differ among studies, what is striking," she said, is the percentage of overweight/obese patients (37%; defined as a body mass index ≥ 85th percentile) "in our 2-decade single institution dataset." This "is nearly identical" to the percentage of patients with excess adiposity – 37.9% (also defined as BMI ≥ 85th percentile) – in an international cross-sectional study, which also identified an association between obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) and psoriasis severity in children, she noted.

"What is clear is the strong association between obesity and childhood psoriasis, as multiple studies, including ours, confirm obesity as a major comorbidity of pediatric psoriasis," Cordoro said. "Both conditions must be adequately managed to reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes for obese patients with psoriasis."

The other study coauthors were Dana Feigenbaum, MD, and Alana Ju, MD. The work was supported by the UCSF Yearlong Inquiry Program. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

This article originally appeared on MDedge.com , part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Medscape Medical News © 2021 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Study Provides Insights Into Pediatric Psoriasis Over Two Decades - Medscape - Jul 08, 2021.

By Warren R. Heymann, MD

February 5, 2020

Vol. 2, No. 5

Patients are attuned to their diets — healthy, unhealthy, or trendy. Unquestionably, certain foods exacerbate specific dermatoses — just ask any dermatitis herpetiformis patient how they fare with a slice of Sicilian pizza. More often the situation is nebulous. When patients ask me random questions, "Do you think kumquats are aggravating my eczema?" my usual response is not to be dismissive, shrug my shoulders, and say "I don't know — let's look it up in PubMed for real references, not Google." (There are references noting that kumquats, as citrus fruits, may aggravate atopic dermatitis by non-IgE mechanisms.) (1)

As stated on the website Healthline: "If you've been involved in the health and wellness world lately, you've likely heard of the keto diet. The ketogenic diet, also referred to as the keto diet, is a low-carb, high-fat diet. With a very low carbohydrate intake, the body can run on ketones from fat instead of glucose from carbs. This leads to increased fat-burning and weight loss. However, as with any drastic dietary change, there can be some unwanted side effects. Initial side effects of the keto diet may include brain fog, fatigue, electrolyte imbalance, and even a keto rash." (2)

The "keto rash" is prurigo pigmentosa (PP), an uncommon dermatosis consisting of a network of erythematous, pruritic papules evolving into reticulated hyperpigmentation with a specific predilection for the trunk. It is seen mostly in young adults, more often in women. Originally described in Japan, there have been an increasing number of reports worldwide. PP progresses through several stages of development, commencing as erythematous macules which evolve to urticarial papules and papulovesicles. Subsequently, the lesions become crusted or scaly. A few weeks later, they spontaneously resolve, leaving behind reticulated pigmentation. The histologic features vary with each stage of lesional morphology (initially a neutrophilic infiltrate, with spongiosis, vacuolar alteration, and late dermal melanophages). Therapy is with tetracycline antibiotics (minocycline, doxycycline) or dapsone. Topical steroids may help pruritus but have little effect on the rash itself. Recurrences of PP may occur.

Image courtesy of Warren R. Heymann, MD

Image courtesy of Warren R. Heymann, MD The cause of PP is unknown. Several triggering factors have been considered: friction from clothing, allergic contact dermatitis, sunlight, and nutritional factors, including dieting, diabetes, and ketonuria. The histologic presence of follicular bacterial colonies supports the theory that prurigo pigmentosa may be a reactive inflammatory response to bacterial folliculitis. Previously, the benefit of treating PP with antibiotics was attributed to the anti-inflammatory effects of the drugs; while that may be true, perhaps in PP, it is really their antibacterial effect that is responsible for the improvement. (3)

Recently, a graduating resident physician of Asian descent presented with an undiagnosed rash on her back of a few months' duration. It was initially red and pruritic. Topical steroids offered little relief. The diagnosis — PP — was immediately apparent. Before I even discussed the nature of PP, she inquired: "I'm trying to take off some weight before my new job. This rash appeared within a few weeks of starting a ketogenic diet. Do you think that had something to with it?"

As Popeye would say — "Well, blow me down!"

PP was initially described in 1971 by Nagashima et al (4); as of the 1990s, ample literature appeared noting the correlation of diabetes, ketosis, and PP, with improvement of the rash with insulin. (5,6) Teraki et al detailed 10 patients with PP. Five were on a diet to lose weight, two patients had a loss of appetite from stress, and in one patient insulin dependent diabetes mellitus developed at the same time as the skin lesions. Ketosis was observed in 8 of the 10 patients. The eruption cleared when the ketosis diminished. (7) Recently, a 17-year-old boy with PP was described, not having ingested carbohydrates for a year. Within a week of adjusting his diet and administering doxycycline, his PP improved dramatically. (8) PP may also accompany bariatric surgery, presumably due to ketosis (9,10)

How ketosis is pathogenic in PP remains to be defined. According to Hartman et al, increased ketone bodies upregulate intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), a phenomenon also seen in lesional keratinocytes of PP, thereby linking ketosis with inflammation. (11) Perhaps this microenvironment alters the microbiome, allowing for growth of the newly recognized intrafollicular bacteria.

I am dedicating this commentary to two icons of my youth who recently passed away — Arte Johnson (of Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In) and Peter Tork (of the Monkees). I find the concept of ketosis and PP verrrry interesting and now I'm a believer. When patients present with PP, dermatologists should inquire about diabetes mellitus, specific dietary changes, and recent bariatric surgery. If patients are at risk for ketosis, dietary carbohydrate supplementation may be all that is needed to alleviate this very interesting eruption.

Point to Remember: There is ample literature to support the association of ketosis (and a ketogenic diet) to prurigo pigmentosa. Correcting the ketotic state is therapeutic.

Harper Price, MD

Division Chief, Pediatric Dermatology

Phoenix Children's Hospital

It is unusual that a day won't go by in our clinics without a patient or their family member asking about the relationship between foods and the skin — whether it be for overall skin health (should I take a hair and nail vitamin?) or specific skin eruptions (e.g., the dreaded — is the dairy causing my eczema or acne?). Although many times the evidence is little to none at best to support our patient's hunches about what might be causing their skin rashes, this is not so in the case of PP. Dietary questioning, especially regarding carbohydrate intake and exclusion, becomes the key to the diagnosis in PP. This is well-supported by the current literature, despite the fact that the role of a ketotic state in the pathogenesis of PP remains to be elucidated. Along with the classic clinical presentation of PP and appropriate patient history, we can reassure our patient of the diagnosis and offer (oftentimes) a non-pharmaceutical treatment plan, especially important in the era of great emphasis on proper antibiotic stewardship and avoidance of polypharmacy.

Brockow K, Hautmann C, Fötisch K, Rakoski J, et al. Orange-induced skin lesions in patients with atopic eczema: Evidence for a non-IgE-mediated mechanism. Acta Derm Venereol 2003; 83: 44-8.

Keto rash: What it is, why it happens, and how to cure it. Healthline, April 30, 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/keto-rash

Heymann WR. Getting within a hair's breadth of understanding prurigo pigmentosa. Dermatology Insights and Inquiries. March 2, 2017.

Nagashima M. Prurigo pigmentosa – clinical observations of our 14 cases. J Dermatol 1978; 5: 61-7.

Murao K, Urano Y, Uchida N, Arase S. Prurigo pigmentosa associated with ketosis. Br J Dermatol 1006; 134: 379-381.

Yokozeki M, Watanbe J, Hotsubo T, Matsumura T. Prurigo pigmentosa disappeared following improvement of diabetic ketosis by insulin. J Dermatol 2003; 30: 257-8.

Teraki Y, Teraki E, Kawashima M, Nagashima M, Shiohara T. Ketosis is involved in the origin of prurigo pigmentosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34: 509-511.

Michaels JD, Hoss, DiCaudo DJ, Price H. Prurigo pigmentosa after a strict ketogenic diet. Pediatr Dermatol 2015 32: 248-251.

Al-Dawsari NA, Al-Essa A, Shahab R, Raslan W. Prurigo pigmentosa following laparoscopic gastric sleave. Dermatol Online J 2019; May 15; 25 (5).

Alshaya MA, Turkmani MG, Alissa AM. Prurigo pigmentosa following ketogenic diet and bariatric surgery: A growing association. JAAD Case Rep 2019; 5: 504-507.

Hartman M, Fuller B, Heaphy MR. Prurigo pigmentosa induced by ketosis: Resolution through dietary modification. Cutis 2019; 103: e10-e13.