PROBING PEDIATRIC PIGMENTED PURPURAS DII small banner By Warren R. Heymann, MD, FAAD October 20, 2021 Vol. 3, No. 42

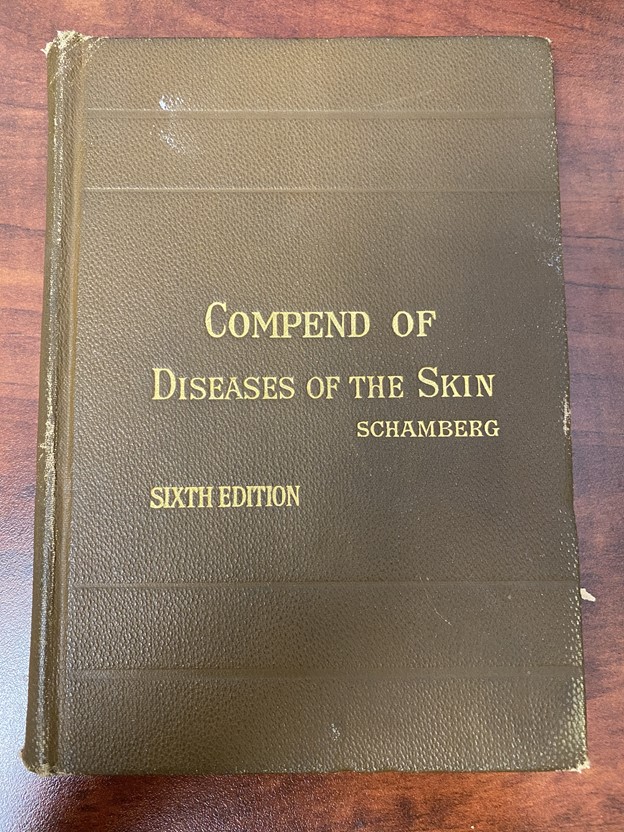

PPs are classically considered as one of 5 types: Schamberg disease (progressive pigmentary dermatosis); pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot‐Blum; purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi disease); lichen aureus, and the eczematoid‐like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis. A sixth type, a granulomatous pigmented purpuric dermatosis, often associated with hyperlipidemia, has been recently described. (1)

Biopsies and/or appropriate serologic studies should be considered when there are other diagnostic considerations such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenström, or cryoglobulinemia.

This commentary will focus on pediatric PP eruptions.

Coulombe et al retrospectively reviewed their experience with 17 patients with biopsy-proven PPs; 8 were male and the mean age of onset was 9 years. PP was asymptomatic in 11 patients, pruritic in 3, and of cosmetic concern in 3. Schamberg's disease was the most frequent subtype in 12 cases. Resolution of PP was found in 13 cases with a median duration of less than 1 year (range 6 months-9 years). Five patients experienced spontaneous clearing without treatment, and improvement was observed in 75% of cases treated with topical corticosteroids and 100% with narrowband ultraviolet B (nbUVB). No associated diseases, significant drug exposure, or contact allergens were found. These findings support that PPs in children are idiopathic, chronic eruptions that can benefit from watchful waiting, although topical corticosteroids or nbUVB may be useful if the patient or family desires faster resolution. The authors acknowledge that their study was limited by its small size, its retrospective nature, and selection and recall bias. (4)

Plachouri et al reviewed therapeutic strategies for PPs, noting that no evidence-based treatments have been found to be dramatically effective for most patients. Most reports are case studies or small case series — the need for prospective studies is readily apparent. Local therapies include compression, topical steroids, and calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic treatments include the flavonoid rutoside, vitamin C, colchicine, pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, systemic steroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Ultraviolet light (nbUVB and PUVA), lasers (1540 nm erbium, 595 pulsed dye), and intense pulsed light combined with photodynamic therapy have all been reported to be beneficial to some degree. (5) I cannot think of another condition where primum non nocere (first do no harm) is more apropos.

Ollech et al performed a retrospective study of the clinical course and utility of vitamin C and rutoside in children with PPs treated at their institution between 2008 and 2018. A total of 101 patients were evaluated. The female : male ratio was 1.3 : 1, and the median age at diagnosis was 8.8 years. Median follow-up was 7.13 months. The most common PP subtypes were lichen aureus (43%) and Schamberg (34%). Fifty-three (52%) patients had evaluable follow-up documentation via their medical record or phone questionnaire. Twenty-eight patients were treated with vitamin C or rutoside or combination therapy. Twenty-five patients received no treatment. Clearance of the rash was noted in 24 (45.3%) patients overall, including 10 (42%) patients in the treated group and 14 (58%) patients in the untreated group. Recurrence was noted in seven (13.2%) patients. One patient with biopsy-proven linear PP evolved into linear morphea several months following clearance of the PP. Treatment with vitamin C and/or rutoside was well tolerated without side effects. None of the patients were subsequently diagnosed with vasculitis, coagulopathy or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The authors concluded that PPs in children are benign dermatoses with high rates of complete resolution. Although treatment with vitamin C and rutoside is well tolerated, there did not appear to be an advantage over watchful waiting without therapy. (6)

Point to Remember: Pigmented purpuric eruptions may be seen in the pediatric population. Although many approaches have been reported as beneficial, these are based on small case reports and series. Tincture of time (watchful waiting) may be a reasonable approach for many patients.

Our expert's viewpoint

Albert C. Yan, MD

Professor of Pediatrics and Dermatology

Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

When I was a Penn resident working with Dr. Jim Leyden, I recall him observing, half-facetiously, that you might want to "hurry up and treat" a particular patient, the implication being that whatever you use will appear effective in a condition that spontaneously remits.

So I am gratified to read this article which highlights the generally benign nature of pediatric pigmented purpuric dermatosis. I have encountered several dozen children with PPD over the years and have been impressed with how some spontaneously resolve while others are resistant to many attempted treatments only to later resolve. This article nicely shows that at least in this retrospective series, not treating — active non-intervention — was as successful as active intervention. Sometimes the best treatment is no treatment at all.

Skin Care Physicians of Costa Rica

Clinica Victoria en San Pedro: 4000-1054

Momentum Escazu: 2101-9574

Please excuse the shortness of this message, as it has been sent from

a mobile device.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home